Hogarth, Roblin M. Educating Intuition. The University of Chicago Press. Chicago, 2001.

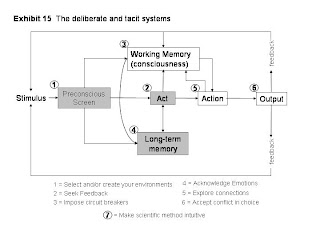

Intuition is that unconscious decision making process that we all are capable of to some extent or another. The question that the author addresses in this book is whether we are capable of actively refining our intuitions. In order to tackle this concept the author had to delve into many aspects of cognition, especially as it relates to the work of experts. He divides our thought processes into two streams: the deliberate and the tacit. The tacit corresponds to the innate reasoning that we generally consider to be intuition. Although we are not actively conscious of it, the author has positioned the steps involved in tacit reasoning in relation to conscious deliberate reasoning and outlined a process by which we can consciously improve our tacit reasoning. The overall map of this process is diagrammed below (from p.196 of the book). Essentially the process involves becoming conscious of tacit reasoning and then selecting experience and feedback that will allow development of that reasoning while being aware of potential cognitive biases (examples given are the regression to the mean and the gambler's fallacy) through what he calls "circuit breakers". He feels that learning can occur in the tacit system once we have consciously learned to apply the scientific method in reflecting on our intuitions, particularly with respect to the use of falsification.

Since I am interested in the Scientific Method and the relationship that intuition has to it, I found it interesting that the author turned the relationship around so that the Scientific Method becomes a way that we can consciously select experiences that train our intuition. Then our intuition leads us to to new insights which can then also be confirmed by the Scientific Method. Once again, I tend to relate these ideas to the deduction/induction process where the "tacit" reasoning corresponds to induction and the deduction to the "deliberate". This book seems to suggest that there is an element to human cognition whereby we are constantly seeking patterns unconsciously, which then are brought, seemingly unbidden, to the fore when we are consciously attempting to understand something.

The diagram of the model and further quotes follow.

p.158

...experts and novices use different problem-solving strategies. Novices tend first to identify a specific goal and then work backward through the details of the problem to find a way to reach the goal. Experts, however, tend first to take in the details of the problem they face, then determine (through a process of recognizing similarities) the general framework that best fits the data, and, finally, work forward from that framework to explore possible solutions (goals). The process that novices follow (working backward) is more deliberate; the process that experts follow (working forward) is more intuitive.

p. 212

...the strength and weakness of tacit learning is the fact that it is tied to what has been experienced . It is necessarily limited. On the other hand, deliberate processes can produce impressive intellectual achievements.

One such achievement -- known generally as scientific method (i.e., the methods and rules of scientific reasoning) -- allows us to learn more effectively from experience.

On a section regarding the testing of intuitive thought, p236-237:

The key advice for testing can be summarized as follows: When you have what you think is a good hypothesis (or belief or idea), ask yourself what could change your mind. What evidence would you need to see to be convinced that you are mistaken?

p.239 "Exhbit 20" Improving skills of testing

1. Get into the habit of searching for possible disconfirming evidence.

2. Continue to generate alternative ideas -- understanding is rarely complete. Ask yourself what you would expect to see if different ideas were true. How can you check these predictions?

3. Be aware that taking action may prevent you from ever being able to check your idea or hypothesis. That is, taking action may prevent you from seeing the outcome of the action that you didn't take. Act, or don't act, but don't fool yourself.

4. When possible, check your ideas with other people.

5. Don't expect to find "smoking guns" -- except in well-defined situations.

6. To what extent are your beliefs in ideas dependent on particular pieces of evidence? How valid is that evidence? How would your beliefs change if that evidence were less reliable or even missing?

7. What evidence would lead you to change your beliefs?

8. Could what you see be due to chance? In whole, or in part? (Recall regression toward the mean and the gambler's fallacy [see pp. 123-125].)

9. To what extent do you want your specific idea to be true? Does this color your understanding?

10. Remember that, in dealing with people, it is usually possible to check ideas or hypotheses only at the level of actual, observed behaviour. We rarely, if ever, have access to underlying motivations.

11. Seek feedback!